Table of Contents

If you work in print, you will hear people say you need RIP software. So what is it, and does RIP stand for anything? Short answer. Yes. RIP stands for raster image processor. RIP software converts your design files into the exact dots your printer lays on paper, film, fabric, vinyl, or metal. It is the translator between creative files and the print engine. And when it is set up well, color is predictable, small type holds, and jobs flow without drama.

RIP software meaning

RIP software takes input like PDF, PostScript, or images and interprets every vector, font, transparency, and pixel into a high resolution bitmap the printer understands. That bitmap is then screened into printable dots, with control over how those dots are placed. This is the core “raster image processing” step. Without it, complex pages with overprints, spot colors, and live transparency would not render correctly on many print devices.

How a raster image processor works

Most RIPs follow three steps that run fast behind the scenes.

Interpretation. The RIP reads the page description language, loads fonts, resolves transparency, and builds an internal object list.

Rendering. It converts that description into a continuous tone raster at the device resolution. Think 600 to 2400 dpi for toner and platesetters, or varied native resolutions for inkjet heads.

Screening. It turns the continuous tone raster into printable dots. You can choose classic AM screening, or modern FM, sometimes called stochastic screening. The choice affects grain, gradients, and moiré.

RIP software also manages queues and memory, so large files do not choke the printer. Good RIP setups use hot folders, presets, and job tickets to keep production consistent.

RIP software vs a printer driver

A basic printer driver is fine for office documents. RIP software exists for control. Control of color, screening, ink limits, white ink layers, varnish and metallic channels, nesting and tiling, cut paths, and precise print queues. That control is critical for wide format, label and packaging, DTG and DTF, dye sub, UV flatbed, and platesetting. RIP software also lets you run multiple jobs in parallel, apply per-media ICC profiles, and automate imposition or panel tiling. You get fewer surprises and less waste.

What “RIP” stands for in printing

RIP stands for Raster Image Processor. Historically it was dedicated hardware sitting between a workstation and an imagesetter. Today it is most often software on a workstation or built into a digital front end. The meaning did not change. It still means the component that turns pages into pixels the engine can fire.

Common RIP features you will actually use

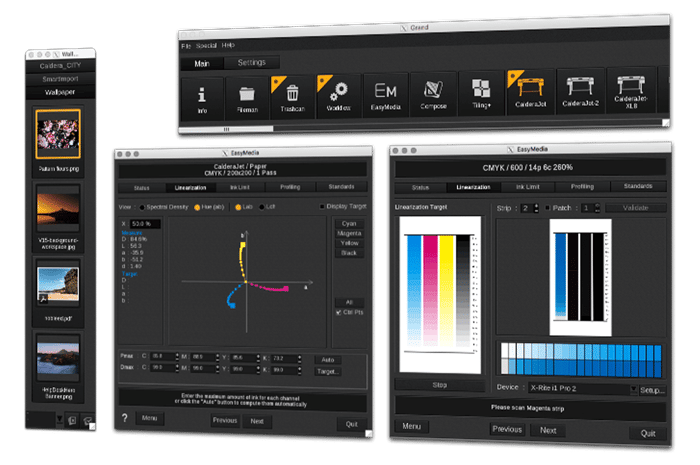

Color management. ICC profiling, device linearization, calibration routines, spot color libraries, gray balance targets like G7.

Screening choices. AM and FM options, sometimes hybrid. Useful for text sharpness and smooth gradients.

White, varnish, and specials. Automatic underbase for white ink, choke and spread, overprint handling, layer ordering for effects.

Nesting, tiling, imposition. Arrange multiple jobs on a roll or sheet to save media. Tiling for oversized graphics.

Queues and hot folders. Standardize settings by printer and material. Drop in a file, get a predictable result.

Preflight and fixes. Font substitution alerts, overprint warnings, hairline fixes, ink limiting, and black generation strategies.

Variable data support. Efficient rendering when only parts of a page change.

Examples you will hear about

You will see names like Adobe PDF Print Engine inside many DFEs, Harlequin RIP in industrial systems, and Fiery servers on production presses. In wide format you will see Onyx, Caldera, SAi, RasterLink, VersaWorks, Wasatch, and more. They all perform the same core job with their own tools for queues, profiles, and UI.

Do you need RIP software

Ask three quick questions.

Do you print color-critical work or specialty inks. If yes, you need device profiling, white and spot workflows, and screening control. That is RIP territory.

Do you run wide format, DTG, DTF, UV, or packaging. These devices expect RIP workflows for nesting, tiling, cut paths, and underbases.

Are you scaling up. If your team needs hot folders, load balancing, and job accounting, a RIP or DFE is the right tool.

If you run an office laser printer or simple photo printer, the vendor driver might be enough. For production, RIP software is a must.

Choosing a RIP without the headaches

Start with your printer vendor. Many machines ship with a recommended RIP or DFE.

Check profile support. Make sure there are ICCs or profiling tools for your media.

Match features to work. White ink, cut contour, varnish, metallic, variable data, and imposition are not universal.

Look at queue and user rights. Production teams need presets, logs, and simple role permissions.

Trial on real jobs. Run your ugliest PDFs, transparencies, tiny type, and spot libraries before you buy.

Quick FAQ

Does RIP stand for anything. Yes. Raster Image Processor.

Is RIP software hardware or software. Both exist. Today, most solutions are software or built into a digital front end.

Is Adobe a RIP. Adobe PDF Print Engine and Adobe Embedded Print Engine are core RIP technologies used inside many devices and DFEs.

Is Fiery a RIP. Fiery servers are digital front ends that include RIP technology, color tools, and workflow features.

What about Harlequin. Harlequin is a long-running RIP used in many industrial and packaging systems.

Bottom line

RIP software is the brain that turns your design into printable dots. It controls color, screens the image, builds special layers, and pushes reliable jobs to your device. If you print professionally, you need a RIP. Call it a raster image processor, call it your DFE. Either way, it is how you get repeatable results.